The Banned Book List: a monument of injustice against freedom of speech | Sue Jeong Ka

Figure 1. The environmental approach, past and present.

“No new jails! Schools, not jails!” On 6 October 2019, I stood on the sidewalk in New York City’s Chinatown as a crowd of activist friends and neighbors chanted these slogans and marched in the street (Narizhnaya 2019). They were reacting to Mayor Bill de Blasio’s announcement of a final plan to close the infamous jail complex on Rikers Island and replace it with four smaller, borough-based jails, including one to be constructed nearby at 125 Center Street (Haag 2019).

After witnessing the protest in October, I began attending informational gatherings organized by citizens against the new jails. The meeting rooms were always filled with people from a wide variety of situations and circumstances: activists, artists, community organizers, lawyers, architects, urban planners, as well as local residents, business owners, and workers. Each of them stood up there for themselves with their own agency to speak. One group, however, always went unrepresented: people currently incarcerated. Where and how could I hear their voices, I wondered. Incarceration, by its very nature, inhibits one’s personal agency (Allred, Harrison, and O’Connell 2013). Simply put, the condition of imprisonment obstructs self-representation and self-knowledge. It prohibits full access to information circulating in the media and to public discourses such as those about new jail proposals. As subjects of the same system of pain, the same carceral state, but with more access, choice, and mobility, those in the US who are not incarcerated have the responsibility to work on behalf of those who are (Rose and Shadowproof 2019). With this conclusion, I started The Banned Book List project (Figure 1).

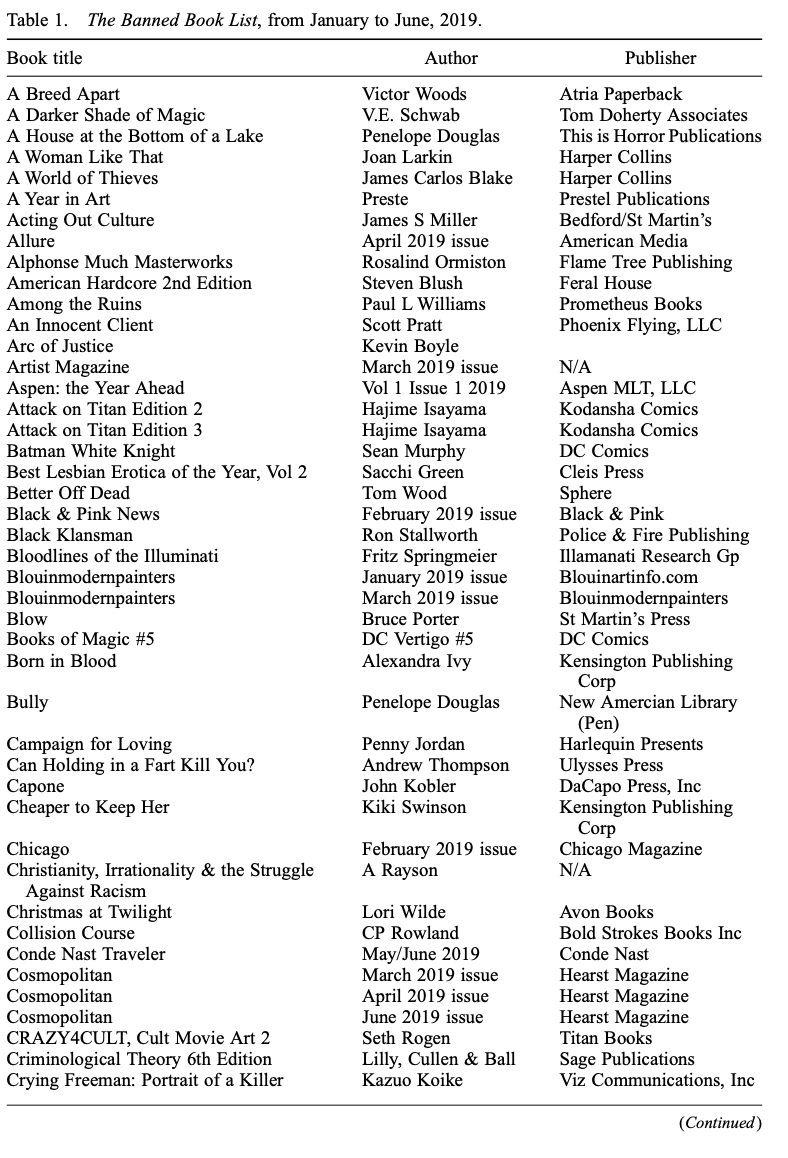

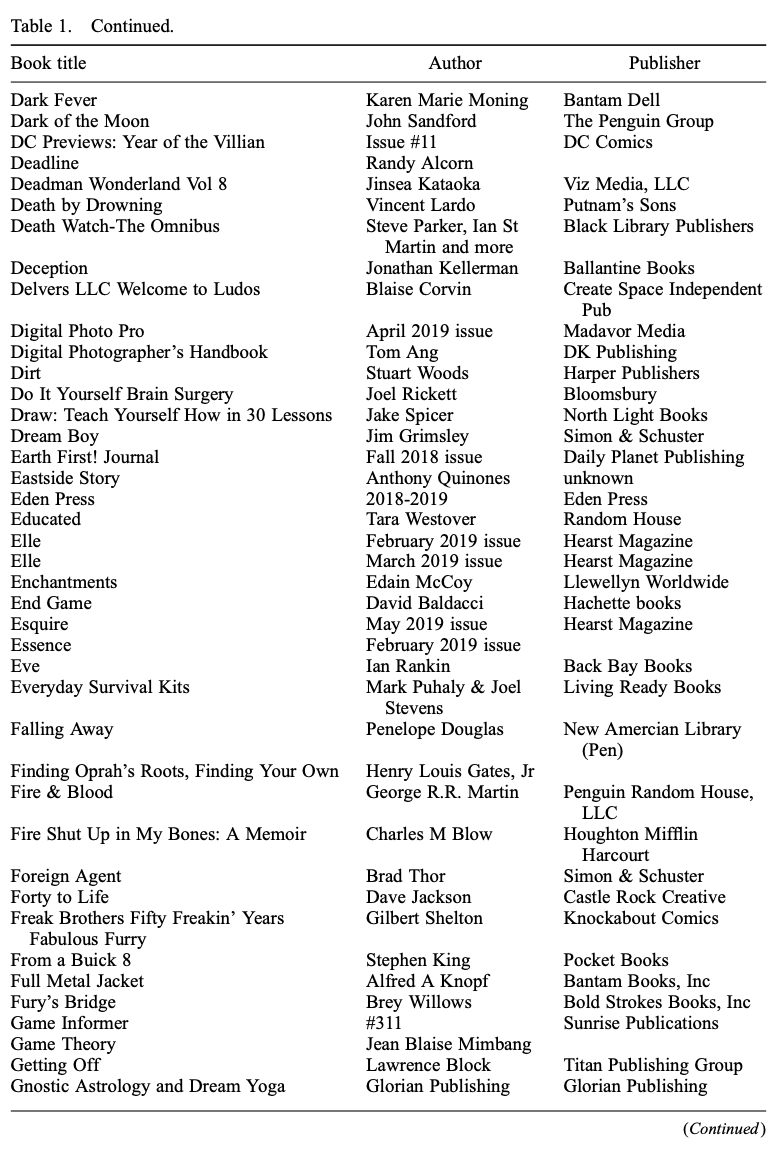

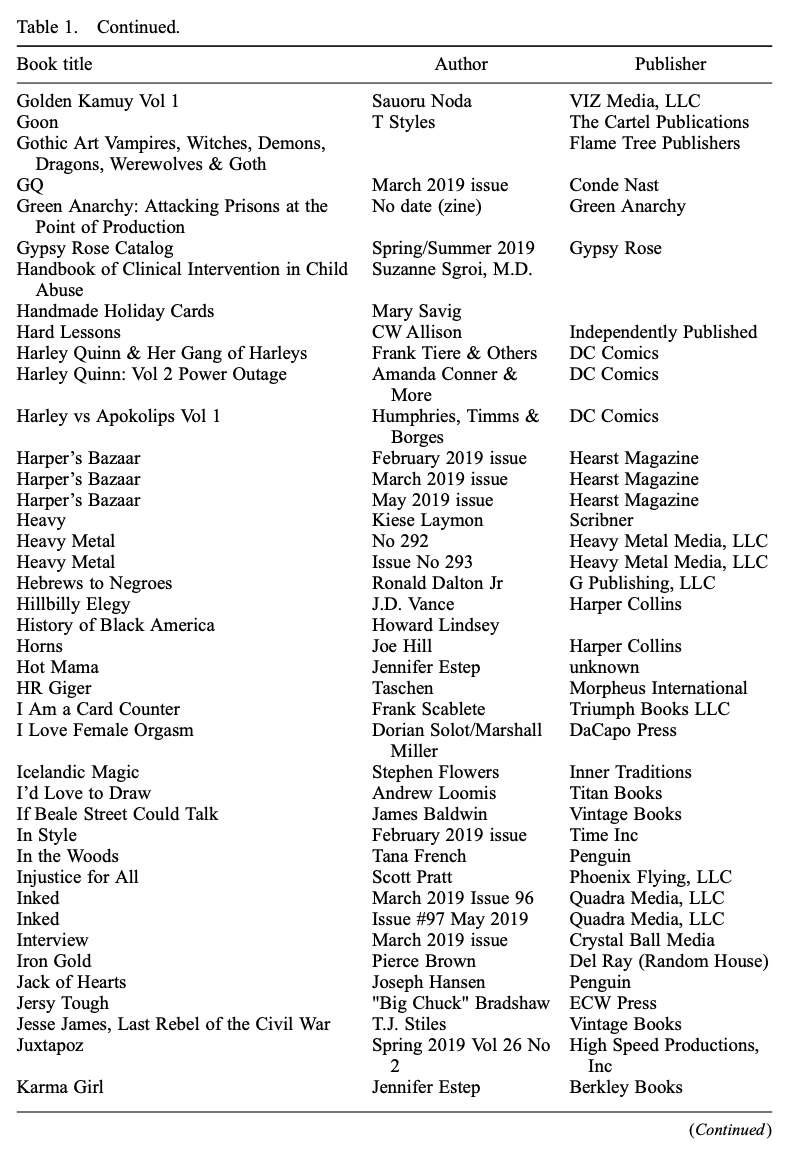

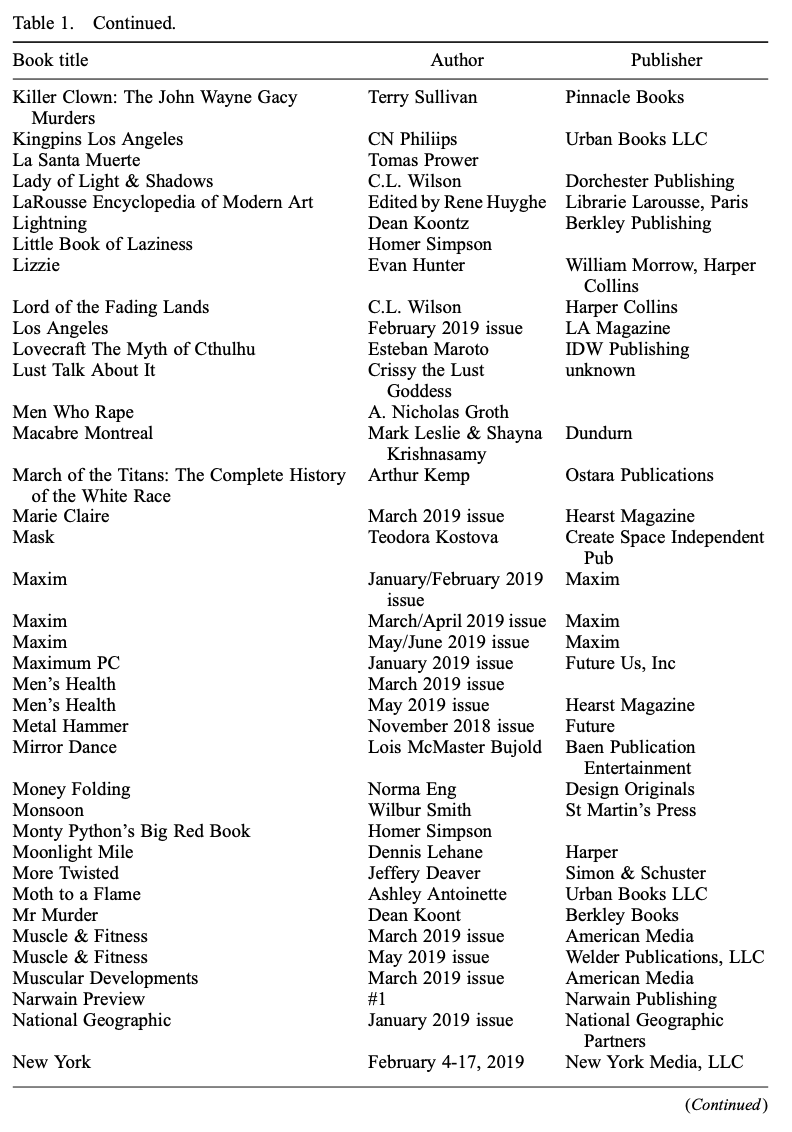

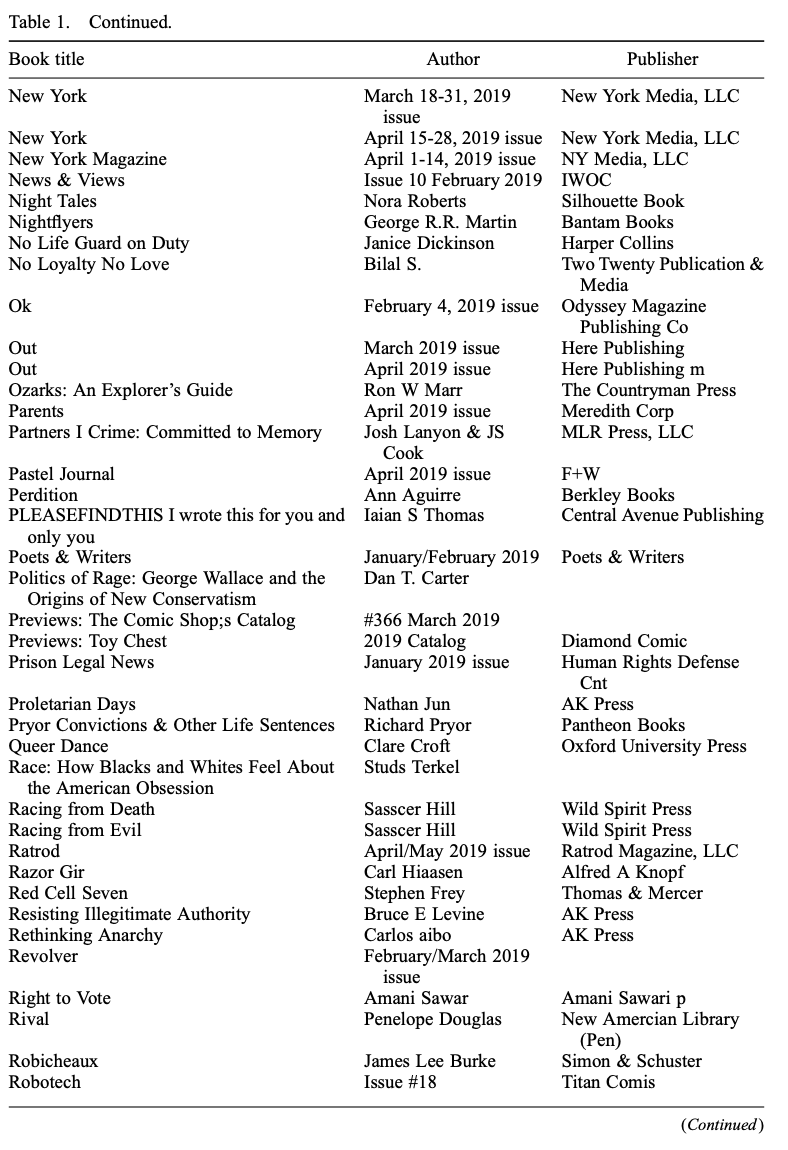

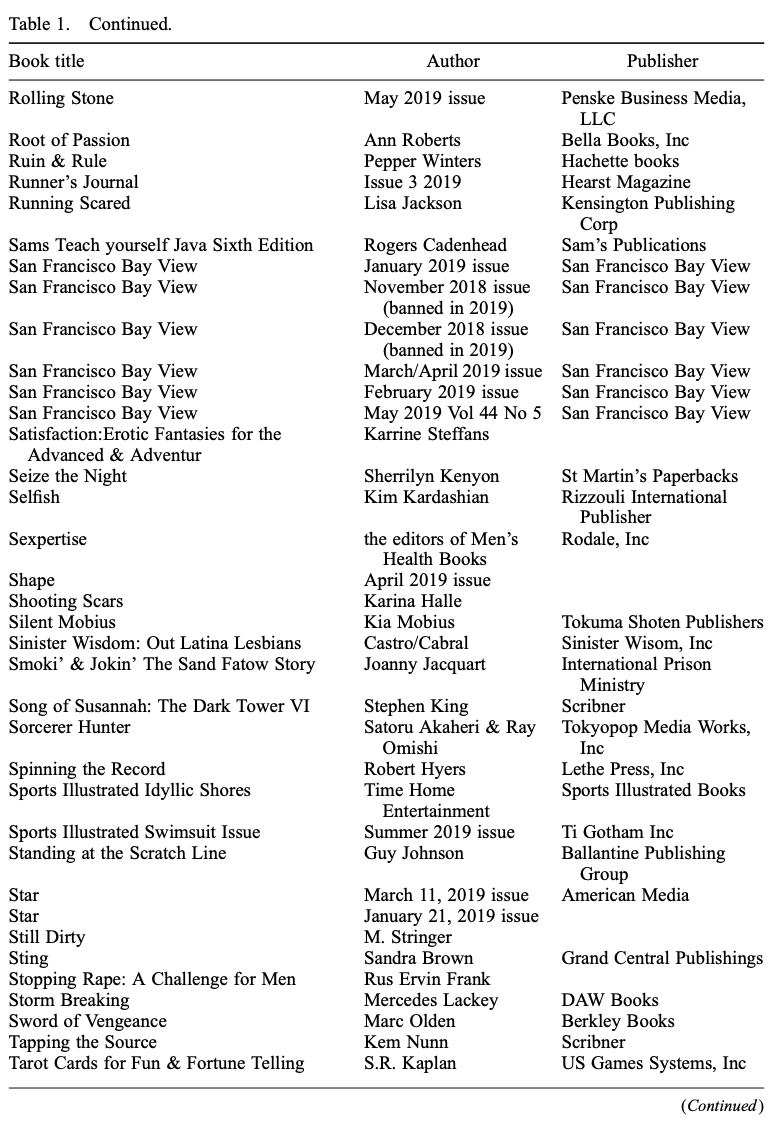

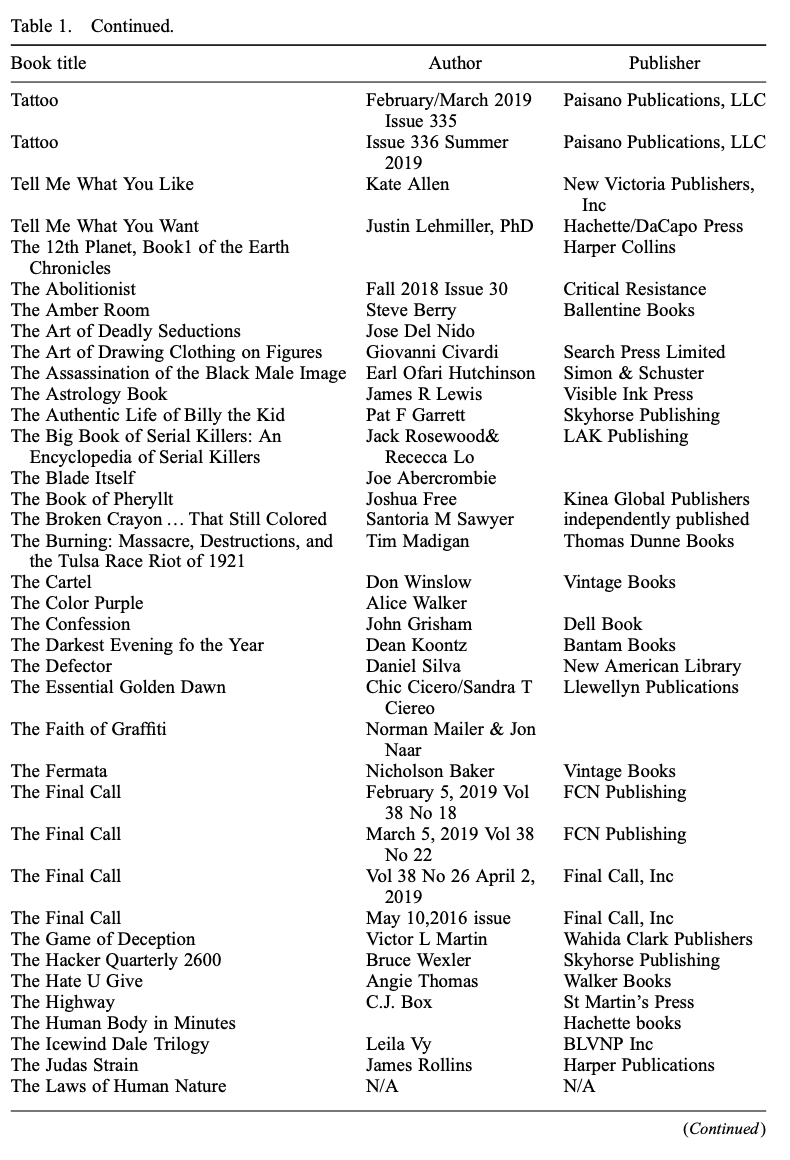

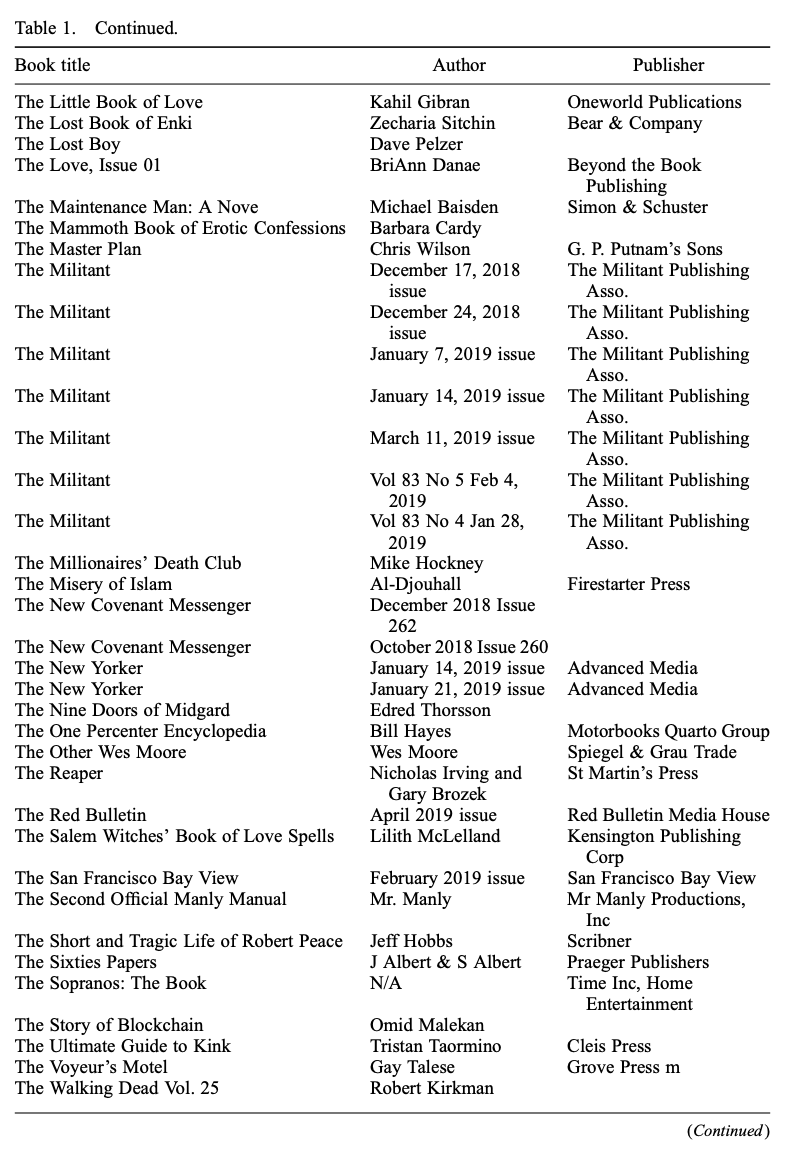

The Banned Book List collects titles that are banned by American prisons (Table 1). It includes hundreds of thousands of books from all categories of literature: classic works of fiction, such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe and If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin; non-fiction books, including Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover; issues of magazines like Vogue and New York; and even children’s literature, such as Where’s Waldo? by Martin Handford. Although prison policies state that banned books pose a potential threat to the security of prison operations, the titles reveal how arbitrarily and liberally the authorities at state and federal correctional institutions censor reading materials that are sent to incarcerated people (Gaines 2020). As long as this list is, it remains incomplete – only 21 of the 50 states disclose their banned-book lists when individuals or entities request them through the Freedom of Information Act.1

Without a doubt, restricting prisoners’ free access to books based on open-ended, possibly biased, “reasonable penological concerns” by prison officials violates their First Amendment rights (Bordan 2018). The rights of incarcerated individuals matter not only because they are one of the most vulnerable groups of Americans – exploited in slave-like conditions under the Thirteenth Amendment – but because their legal position can function as a basic parameter of human rights in an era of mass incarceration and during the economic crisis that is American neoliberal capitalism (Pope 2019). As Justice Thurgood Marshall stated in Procunier v. Martinez,

When the prison gates slam behind an inmate, he does not lose his human quality; his mind does not become closed to ideas; his intellect does not cease to feed on a free and open interchange of opinions; his yearning for self-respect does not end; nor is his quest for self-realization concluded.3

notes

-

The 21 states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylva- nia, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. ↩

-

Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987). ↩

-

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974). ↩

notes on contributor

Sue Jeong Ka’s work seeks to meet communal needs. From commemorations of female Asian immi- grants from the 19th century to a trilingual community newspaper and a piece assisting queer and immigrant homeless youth in New York apply for federally issued IDs, she mobilizes traditional art spaces to provide community services and in so doing to critique the public structures in which we exist. She is an alumna of the Whitney Independent Study Program (NY, US) and a recipient of Gail and Stephan A. Jarislowsky Outstanding Artist Fellowship (Alberta, CA), LMCC’s Creative Engagement Grant (NY, US), the NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship (NY, US), The Laun- dromat Project’s Create Change Fellowship (NY, US), and has been in residence at the Banff Center for Arts and Creativity (Alberta, CA), The Drawing Center (NY, US), Studio in the Park, Queens Museum/ArtBuilt (NY, NY), Soma Summer (Mexico D.F., MX) among many others. Currently, Ka is researching the history of carceral architecture in NYC’s Chinatown in support of Asian/ Pacific/American Institute at New York University and the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm.

References

Allred, Sarah L., Lana D. Harrison, and Daniel J. O’Connell. 2013. “Self-efficacy: An Important Aspect of Prison-based Learning.” The Prison Journal 93 (2): 211–233.

Bordan, Tess. 2018. “New Jersey Prisons Reverse Course on Banning ‘The New Jim Crow’ After ACLU of New Jersey Letter.” The ACLU New Jersey, January 10. https://www.aclu.org/blog/ prisoners-rights/civil-liberties-prison/new-jersey-prisons-reverse-course-banning-new-jim-crow.

Gaines, Lee. 2020. “Who Should DecideWhat Books Are Allowed In Prison?”NPR, February 22. https:// www.npr.org/2020/02/22/806966584/who-should-decide-what-books-are-allowed-in-prison.

Haag, Matthew. 2019. “N.Y.C. Votes to Close Rikers. Now Comes the Hard Part.” The New York Times, October 19. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/17/nyregion/rikers-island-closing-vote.html.

Narizhnaya, Khristina. 2019. “About 250 Protest Proposed New Jails in Lower Manhattan.” The New York Post, October 6. https://nypost.com/2019/10/06/about-250-protest-proposed-newjails-in-lower-manhattan/.

Pope, James Grey. 2019. “Mass Incarceration, Convict Leasing, and the Thirteenth Amendment: A Revisionist View.” N.Y.U. L. 94: 1465–1554.

Rose, Jennifer, and Shadowproof. 2019. “Why I Support Closing Rikers Island without Building New Jails: A Letter from Prisoner Jennifer Rose.” Shadowproof, November 19. https:// shadowproof.com/2019/11/19/why-i-support-closing-rikers-island-without-building-new-jailsa-letter-from-prisoner-jennifer-rose/.