Dissidence, Dissidance: Claude Cahun & Marcel Moore's Visions and/in Oxana Chi's Motions | Layla Zami

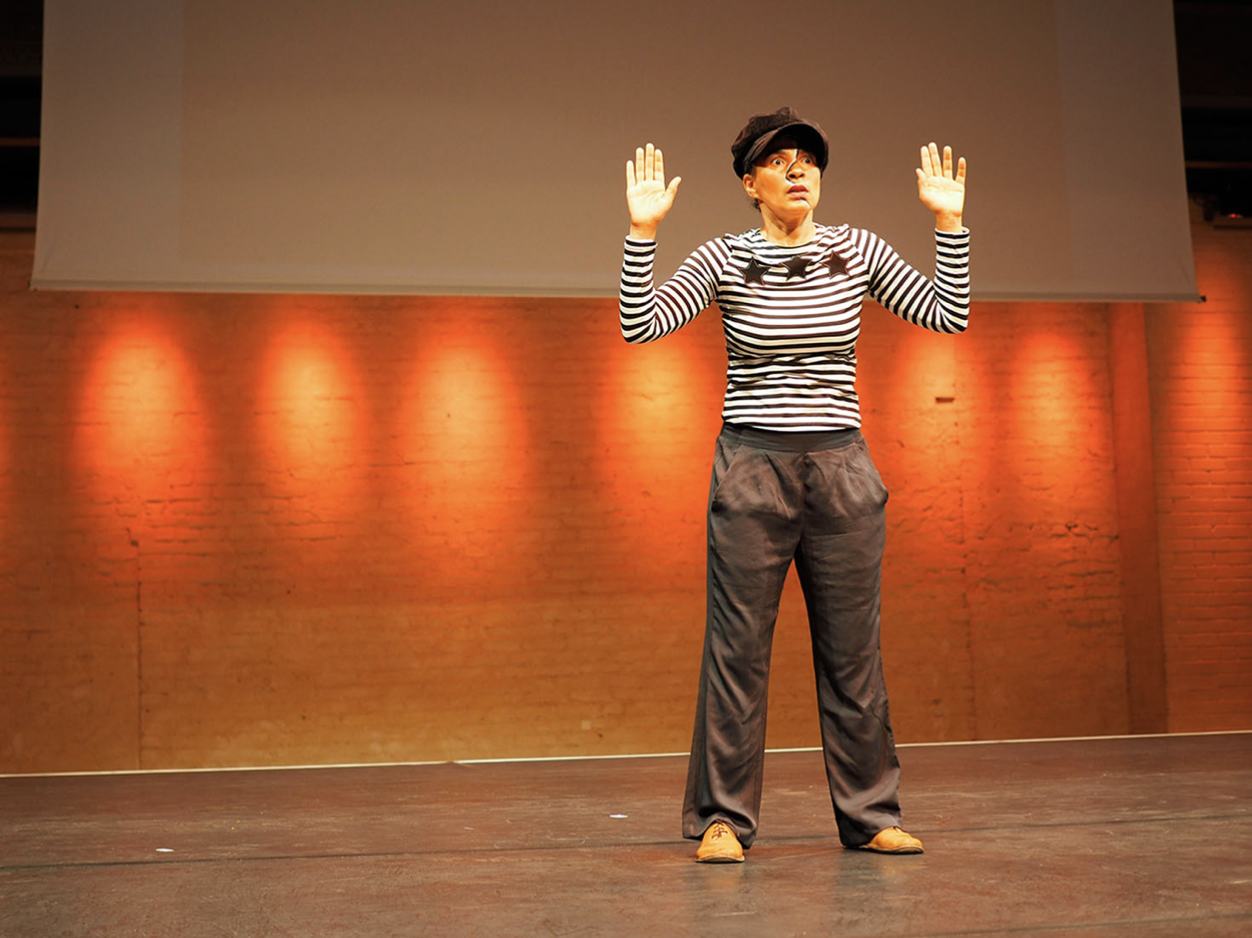

Here German dancer-choreographer Oxana Chi can be seen in her dance performance Killjoy, a tribute to the French artist-activists duo Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.1

A simple shift in the letters, a corporeal alchemy transforming the “e” into an “a”. Dissidence becomes dissidance.

Oxana Chi is trained in anthroposophic Eurythmy, dancing from one letter to another is not foreign ground to her. Her dance reunites the realms of physical, intellectual, psychological, and spiritual dissidence.

To be seen, to be [on] scene.

To be sung?

The EYE often comes in pairs.

The collaboration between Claude Cahun and her life partner Marcel Moore.

The collaboration between Oxana Chi and her wife Layla Zami.

Everpresent, but often invisibilized.2 This is the trajectory of many queer collaborations in art and activism.

Cahun’s (1894–1954) and Moore’s (1892–1972) collaboration span across decades,kilometers, and mediums of expression. Nantes, Paris, Jersey ... the 1920s, the 1930s ... photography, performance, performative writing, collage, illustration, fashion, publication.

Vision-centered, visionary art-activism.

Cahun-Moore’s image-performances in black and white stage a liberated, androgynous body, who affirms the neuter gender.

Who can be seen on their photos – and how? Feminist art practices sometimes transform tools of oppression into vehicles of freedom. The camera apparatus, initially invented to take (souls), to copy (art works), to archive (lives), can be re-designed, to create (meanings), to stage (emancipation), to invent (life). The camera, which Ariella Azoulay calls the “product of imperialism’s scopic regime” (2018). She writes:

One of the most important of [the camera’s features] is the opportunity that the camera creates for people to coincide with others in the same space and time and thus participate in generating something in common, something that could not be produced otherwise – that is, without the presence and participation of others. It is only through powerful institutions such as museums, archives, the press, or the police, as well as economic and political sanctions, that such other features and the participation of the many are devalued, prohibited, or outlawed in an attempt to deprive the participants in the photographic event of their rights and power, making photography subservient to the imperial project. (2018).

The camera was a central tool of artistic production in the oeuvre of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. A century earlier, in 1919, they had published Vues et Visions, (Views and Visions), an innovative work juxtaposing Cahun’s words and Moore’s illustrations. In 1930, the duo publishes Aveux Non Avenus (Disavowals), an experimental surrealist auto-biography with texts and spiritually powerful photocollages. The eyes, the mirror, watching one another, is it a tender look or a controlling gaze? Always the gaze back at the viewer. A perpetual performance of dragging masks that need to be shed to uncover the true self, still disguised.

The first page of Aveux Non Avenus starts as follows:

*The invisible adventure.

The lens tracks the eyes, the mouth, the wrinkles skin deep ... the expression on the face is fierce, sometimes tragic. And then calm – a knowing calm, worked on, flashy. A professional smile – and voilà!

The hand-held mirror reappears, and the rouge and the eye shadow. A beat. Full stop. New paragraph (Cahun 1930, 1; my translation).3*

When I open the lecture-performance Killjoy with a contextualizing talk about the biography and legacy of Cahun and Moore, I perform the final sentence of this paragraph, as a hyphen between the spacetime of the lecture and the one of the performance. Oxana Chi’s performance-images show her in a black and white costume. She dances vignettes inspired by the photographic oeuvre of Cahun and Moore, and by her own spiritual connection to their figures. There is a postmodern anachronism in the juxtaposition through which she embodies Cahun to a resolutely contemporary soundtrack, which at times include African-American voices on current societal topics. A scene mimicking a police interpellation also opens up questions for the audience, representing what could be either the arrest of Cahun and Moore in the 1940s and/or a moment happening right now. It quickly becomes clear that her dissidance is not merely about the past, but very much about the present urgency of resistance against discrimination, police violence, and other oppressive realities.

Oxana initially created the performance Killjoy as a commissioned work for professor Dr Lann Hornscheidt, a co-founder of the Center for Transdisciplinary Gender Studies at Humboldt-University. The piece premiered at Galerie Funke in Berlin in 2012, in the realm of a symposium on “Trans_Forming Politics” and its companion exhibition entitled: to dyke_trans | dis_visualizing re_locating de_silencing featuring photo and video works by Zanele Muholi, Claude Cahun, Anne Weber, Lann Horscheidt, and the author, among others. Following this initial iteration, the dance became a lecture-performance that raised much interest in academic feminist circles across the globe from Europa-University Adriana to New York University by way of Goldsmith University London, the Feminist Antifascist Congress in Potsdam, and a Conference of European Jewish Women Activists, Academics, and Artists in Serbia. Recently, Oxana Chi created a film centered on the performance Killjoy, as a commissioned work for the exhibition Lila Wunder held in the Fall 2020 at the Queeres Kulturhaus in Berlin, Germany, which addressed themes of (in)visibility for female artists in the 1920s and 2020s.

If you go to the Brooklyn Institute of Social Research’s website, you will find that the institute offered a seminar on Sara Ahmed called Feminist Killjoy, advertised with a painting displaying a figure in black-and-white stripes, reminiscent Oxana Chi’s costume in our lecture-performance Killjoy. As I explain in our lecture-performance, Oxana Chi actually drew inspiration from Sara Ahmed’s notion of “feminist killjoy,”4 itself inspired by the Ghanian novelist Ama Aita Aidoo and her novel Our Sister Killjoy. Ahmed discusses the figure of the dissident, literally the one who sits apart. Shirley Chisholm exhorted “if they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” Claude Cahun, not always given a seat at the table of the Surrealist male elite in France, can be said to have turned the table upside down, and as antifascist activist, she surely would not mind sawing chairs down. Oxana Chi, in a diplomatic move, circumvents the table, forcing everyone to pause, think and wonder, de-centering the focus of attention and decision from the table to the stage.

Addressing the feminist killjoy as one who is seen as “getting in the way” of certain forms of hegemonic happiness, Ahmed describes how the simple “arrival” of a feminist killjoy “into a room is a reminder of histories that ‘get in the way’ of the occupation of that room” (2010). Cahun and Moore “got in the way” of the German occupation. They were bold enough to write pamphlets in German and to make activist and artistic efforts to incite soldiers to rebellion, to dissidence. A photograph from 1945 shows Claude Cahun provocatively holding a Nazi badge between her teeth, after they both survived war and prison.

In Ben Okri’s novel The Freedom Artist, all humans are born in prison, and what is called “civilization” eventually makes them forget this truth. Yet, the question “Who is the prisoner?” appears repetitively, painted, stenciled, spray-painted on all kinds of surfaces, haunting humans who think that they are free.

In 1931 or 1932, years ahead of their imprisonment, Cahun & Moore created the haunting image I Extend My Arms. The body, the face, can’t be seen, they are cast in stone. On this representation of a human locked up in stone, or turned stone, one can only see the extended arms, reaching out through two openings, searching for someone to hug?

For Okri, “Storytellers sometimes see things before they have been experienced” (Okri 2020, 117). If so, which vision does Oxana Chi, who diasporically shares with Okri a Nigerian Igbo heritage, anticipate for the twenty-first century? Which story can Killjoy let us see before we have collectively and individually experienced it? Here is the power of what I call dissidance, namely an embodied, corporeal storytelling that may anticipate, convey, envision, and enact a future moment. Because the liminal space between the performativity of language and the performativity of the staged body is at the core of Cahun’s legacy, I find that the term dissidance enriches the understanding of both Chi’s innovative movement creation and Cahun and Moore’s historical work. In a way, we may say that Cahun and Moore strove to dissidance all of their lives – be it in their visual or performative practice. Today, Chi’s Killjoy activates their art historical heritage, and infuses the act of resisting with movement. Her performance lets us realize that in the twenty-first century, it does not suffice to sit apart. In the age of surveillance, dissidance is an invitation to get up, forget the chairs and the table, and get moving. It is a call to re-invent our relation to each other, to society, and to futurity.

There is so much more to say and especially to view in Claude Cahun’s and Marcel Moore’s work, as in Oxana Chi’s. But I wrote enough for the realm of this contribution. As I write these words, Oxana invites me to pause and join her in observing a minute of silence. She just received an electronic reminder from a feminist friend in Berlin, Germany. Today is April 19, marking the anniversary of the liberation of Ravensbrück, the largest concentration camp for women in Nazi Germany. Each year around that date, many women- and trans-identifying activists and artists organize commemorative events throughout the weekend, in Ravensbrück and elsewhere in Germany.

While we rejoin in silence, our eyes closed, holding hands, I think of our walk today in the park, disrupted by the loud sound of a megaphone. No, it wasn’t the police asking people to stay six feet apart to avoid being infected by the virus that is as invisible as the inescapable digital surveillance of our beings. It was a Black man, across the street, being his own channel of “news.” As I make efforts to listen to the voice reaching us from afar, I come to understand the words “implantable microchips.” I realize that he is trying to warn people of the dangers of radio-frequency-identification (RFID), a subdermal technology that gives goosebumps.

I also think of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, who were arrested in 1944 and sentenced to death for having listened to the BBC and for their resistance to fascism. I remember the soundtrack of Oxana Chi’s Killjoy, a creative experiment with radio frequencies, interspersed with snippets of music with socially conscious lyrics by contemporary African-American and French-Malgache artists.

In her tale of surveillance, resilience, and dissidence, Oxana Chi dances her way out of the oppressive tentacles of the media-medicine-military complex. In the footsteps of Claude Cahun & Marcel Moore, her performance, along with my lecture, envisions queer-feminist pathways to memory and art history. Unfolding many layers of her stories, we hope to give visibility to new possibilities.

Notes

- See Chi (2012), http://oxanachi.de/productions/kill-joy.html

- The product of Cahun and Moore’s collaboration has long been presented (in exhibitions and publications) as the sole authorship of Claude Cahun, and many images taken by Marcel Moore, or by both authors, have been and continue to be archived and displayed as self-portraits. However, current scholars such as Tirza True Latimer have amply demonstrated the fact that their art was often the result of a collaborative process, as documented for instance by labels on negatives and letters. See, for example, Latimer (2006).

- “L’aventure invisible. L’objectif suit les yeux, la bouche, les rides à fleur de peau ... L’expres- sion du visage est violente, parfois tragique. Enfin calme – du calme conscient, élaboré, des acrobates. Un sourire professionel – et voilà ! Reparaissent la glace à main, le rouge et la poudre aux yeux. Un temps. Un point. Alinéa.”

- See Ahmed (2010).

notes on contributors

Dr. Layla Zami is an interdisciplinary artist and scholar, currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Humanities and Media Studies at Pratt Institute. Her work orbits around the intersection of cultural memory, historical trauma, gender/race/diaspora studies and spacetime. Born in Paris, France in 1985, Zami holds a PhD in Gender Studies from Humboldt-University in Berlin, Germany, where she also earned a Teaching Award. Publications include Contemporary PerforMemory (transcript, Critical Dance Studies, 2020). Zami is a Resident Artist with Oxana Chi Dance Art, and a Co-Curator at the International Human Rights Art Festival.

orcid

Layla Zami http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1613-5199

references

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. ““Feminist Killjoys (And Other Willful Subjects).” In “Polyphonic Feminisms: Acting in Concert.”.” The Scholar and Feminist Online 8 (3), http://sfonline.barnard.edu/ polyphonic/print_ahmed.htm.x

Azoulay, Ariella. 2018. “Unlearning Imperial Sovereignties.” Verso, October 24. Accessed April 19, 2020. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4096-unlearning-imperial-sovereignties

Chi, Oxana. 2012 “Killjoy.” Oxana Chi Dance & Art. http://oxanachi.de/productions/kill-joy.html

Latimer, Tirza True. 2006. “Entre Nous: Between Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 12 (2): 197–216. doi:10.1215/10642684-12-2-197

Okri, Ben. 2020. The Freedom Artist. Brooklyn, NY: Akashik Books.